|

In a previous blog post I mentioned my walks in the forests at the edge of the Wollemi National Park during a 2014 artist residency at BigCI. It was not all walking though. There was a lot of clambering up and down the rocks and making my way through the thick undergrowth. Often I sat on the rocks for hours; contemplating, meditating till the insects and birds drew nearer thinking I was part of the natural flora and fauna. And of course I filled pages and pages of sketchbooks with drawing and scribbling.

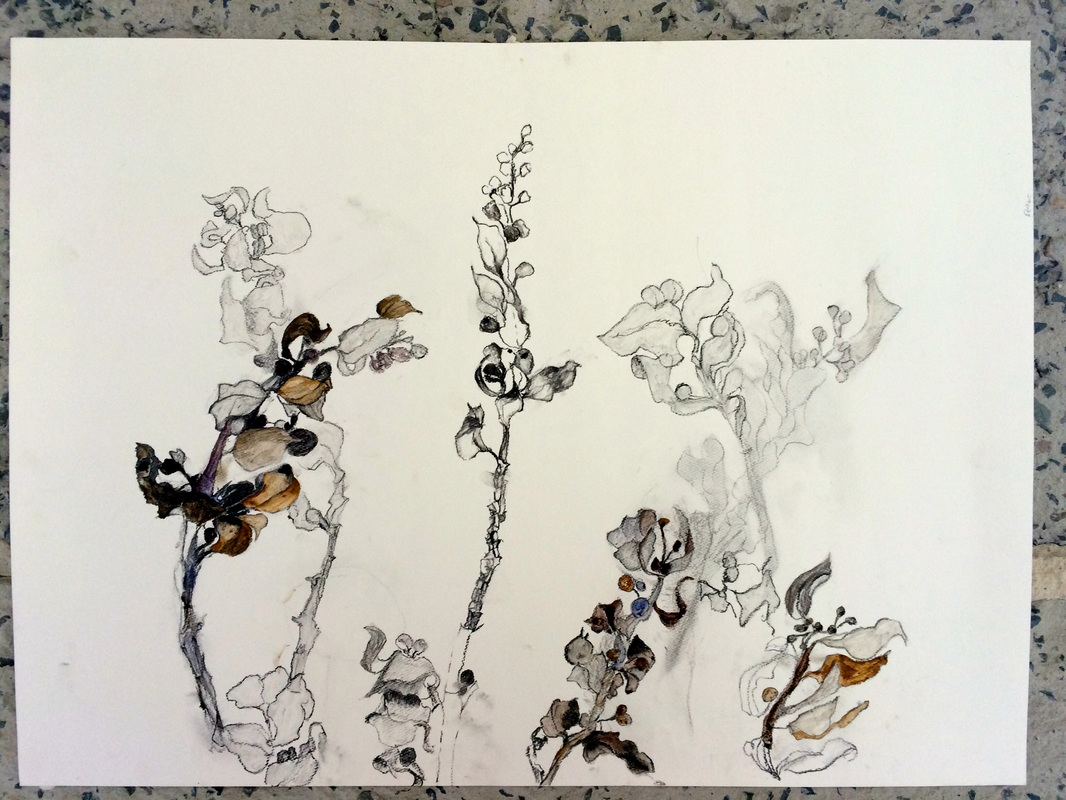

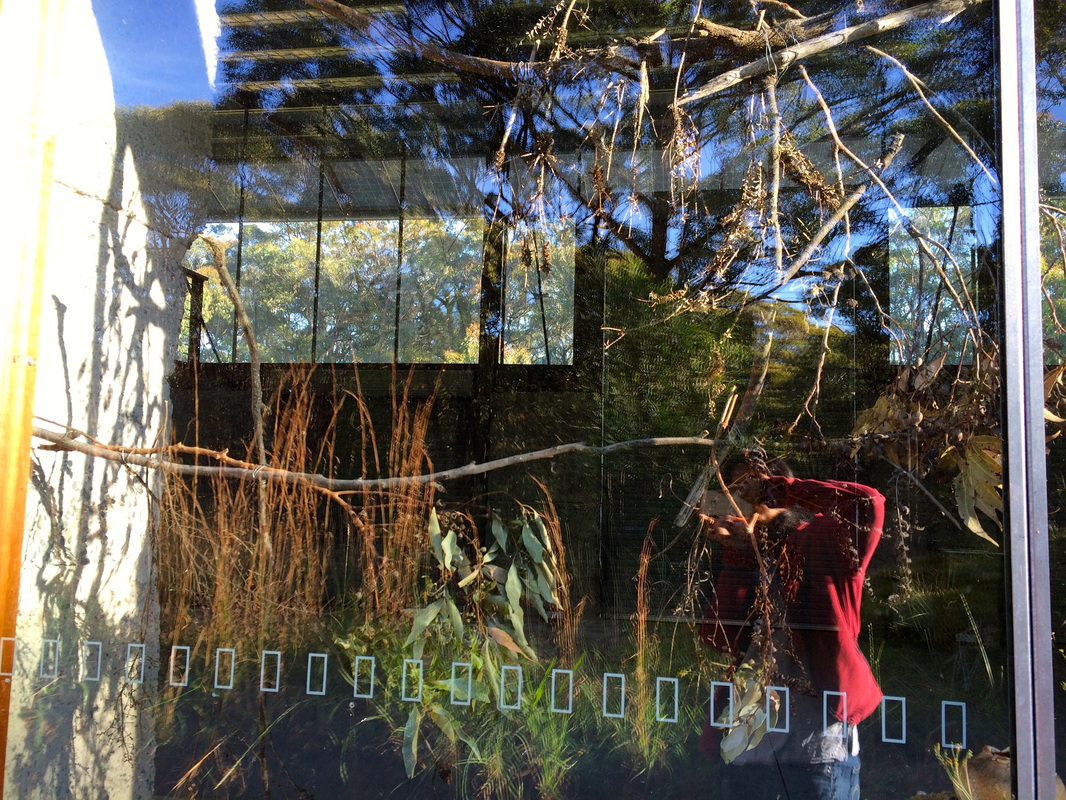

Over time one subject that kept showing up in my sketchbook was the fascinating plant life. I loved some of my drawings but others did not have that “feeling” that had inspired me to draw them in the first place. I had to ask myself what was this essence that I was trying to capture on my sketchbook page. And then it came to me. These plants, wild and chaotic as they were, seemed to grow in accordance with an internal order, a grace that is so obvious to see yet hard to put into words. This astounding array of plantlife is the outcome of centuries of adapting to the environmental conditions in the region, every mutation leading to another new variety. (In my last blog post I mention that this part of the world has the largest variety of flora in the world after the Amazon Basin) Even as I walked around I saw evidence of adaptation and resilience everywhere. In many places one can still see the ground charred black by recent bush fires but a green forest had sprung up over it. I saw tall trees growing leafy and abundant at the top but with their entire trunk hollowed out by fire. I saw some trees growing on other trees that were rooted in the rock-no deep roots to sustain the enormous structures. Resilience perhaps is the source of their wild beauty? In every moment their growth patterns are dictated by the environmental conditions that they sustain and overcome. Flexibility in adapting to their surroundings manifests itself in a grace that is visually perceptible. Something else about these plants also left a lasting impression. As I walked around I saw how plants in the wilderness blossom and flourish in their fullest splendor. But when I walked by the same spot on the next day I would be shocked to find that what had caught my attention yesterday was often lost forever or completely changed by the forces of nature. The abundance flourishing in the face of inevitable transience gave me pause for thought. Some of the walls of the Art Shed at BigCI are made of whiteboards –the same whiteboard that we use in our offices and schools to present our thinking to an audience. Whiteboard and whiteboard markers are a hard, cold, industrial material so different from the organic materials I gravitate towards in my work. Yet the fact that something drawn on a whiteboard is erased in seconds made this material appropriate for what I had to express about these experiences. I painstakingly recreated my sketches on the huge whiteboard wall. Seeking to recreate the intangible rhythm of the forest with whiteboard markers was a challenging experience. The process was a personal journey of attempting to reconcile my urban existence with the lessons I learnt from nature. As I gave my self over to the process, the experience changed me forever. |

|

|

To view the finished work click here.

1 Comment

To view the finished work click here

Walter De Maria, The New York Earth Room, 1977. Long-term installation at 141 Wooster Street, New York City. Photo: John Cliett. Copyright Dia Art Foundation Walter De Maria, The New York Earth Room, 1977. Long-term installation at 141 Wooster Street, New York City. Photo: John Cliett. Copyright Dia Art Foundation City life today is lived largely indoors with a lot of involvement in "non-physical worlds". By non-physical worlds I mean the worlds we enter when watching television, working on the computer, browsing the internet or talking on the phone. Rebecca Solnit calls this an “excess of interiority”. By this she means that we are losing contact with the physical world outside of the worlds created by the gadgets in our homes and offices. This loss of contact in turn results in an obliteration of our relation to our material origins and even to our own bodies. We no longer experience our own body as a natural system integrated with other natural systems. For example, our morning coffee is consumed without a thought to the myriad natural processes that go into the making of each cup (where the bean was grown, the weather, the soil, where the milk, sugar, water comes from, and so forth). Our inability to see our life in connection to these processes makes the cup of coffee a potent representation of how nature is absent from our awareness. Experiencing substance as a way of connecting with natural origins Some artists, instead of using scenes as reminders of nature, use substance as the bearer of meaning. Celebrating the physicality of substance unravels alienation from the natural world. One of my favourite examples is Walter de Maria’s Earth Room (1977, earth, Dia Art Foundation, New York). It is made up of 250 cubic yards of earth (197 cubic meters) 3,600 square feet of floor space (335 square meters) 22 inch depth of material (56 centimeters) Total weight of sculpture: 280,000 lbs. (127,300 kilos) . The New York Earth Room has been on long-term view to the public since 1980. This work was commissioned and is maintained by Dia Art Foundation. It is a reminder that earth is the substance that has been hidden by urbanization and washed away by modern sanitation. For many city dwellers ideas about nature come from video footage in blockbuster movies and calendar photographs. They imagine a place that is pristine and virgin, something that will be defiled if it comes in contact with human presence. Venturing out of urban sites, some may experience disappointment that the countryside is not always the picture perfect idyll they have been led to expect.

The Earth Room, made up of a huge quantity of mud, requires constant tending and replacement to keep it moist yet not growing fungus, etc. Its power lies in the tension between the repulsion we feel for dirt and the pedestal we put art on. At a deeper level earth bears connotations of fertility and decay- aspects of life and death that technological advancement can influence only to a limited extent. It reminds us that our bodies will return to the earth when we die- to the very dirt that we shun during our lifetime. Works such as these remind us that nature is not just a pretty picture to be looked at. It is also more than a life support system. It is that from which our very existence springs and into which it will be absorbed. |

AuthorNandita Mukand is a Singapore-based artist. Her work deals with the relationship with Nature and spirituality from within the contemporary urban context. She employs materiality to question the impact urban life has on our experience of time and the meaning we give to our own existence. Archives

December 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed